For much of the twentieth century, architecture bowed to the logic of function first. Louis Sullivan’s 1896 maxim, “form follows function,” became the mantra of modernism and the fuel for the stripped-down efficiency of the 1920s and 30s. Beauty was measured in precision, not emotion.

Humour and creativity were treated as distractions from truth.

But a purely functional building can be efficient and soulless at the same time. It serves, but it rarely speaks.

As Alain de Botton observes, architecture is “a mirror of our inner world.” Wit in architecture restores that mirror. It interrupts predictability, adds lightness, and reminds us that buildings aren’t just for living in—they’re for living with. Whether a playful façade, a surprising detail, or an ironic use of space— wit reminds us that design is a conversation, not a calculation.

Ben Channon, in Happy by Design (2018), reinforces this human dimension: buildings should make us feel good, not just function well. “sometimes architecture’s role is simply to add little sparks of joy to our everyday existence”. Wit does precisely that—it provokes small moments of joy, curiosity, and recognition. It brings the psychological back into the physical.

Movements that resisted pure functionalism understood this instinctively. Postmodern architects in the 1970s, like Robert Venturi and Michael Graves, used irony and play to challenge the austerity of modernism. Today, the turn toward biophilic and human-centred design continues that rebellion in softer tones—using light, material, and humor to reconnect people to place.

Wit doesn’t abandon utility; it enriches it.

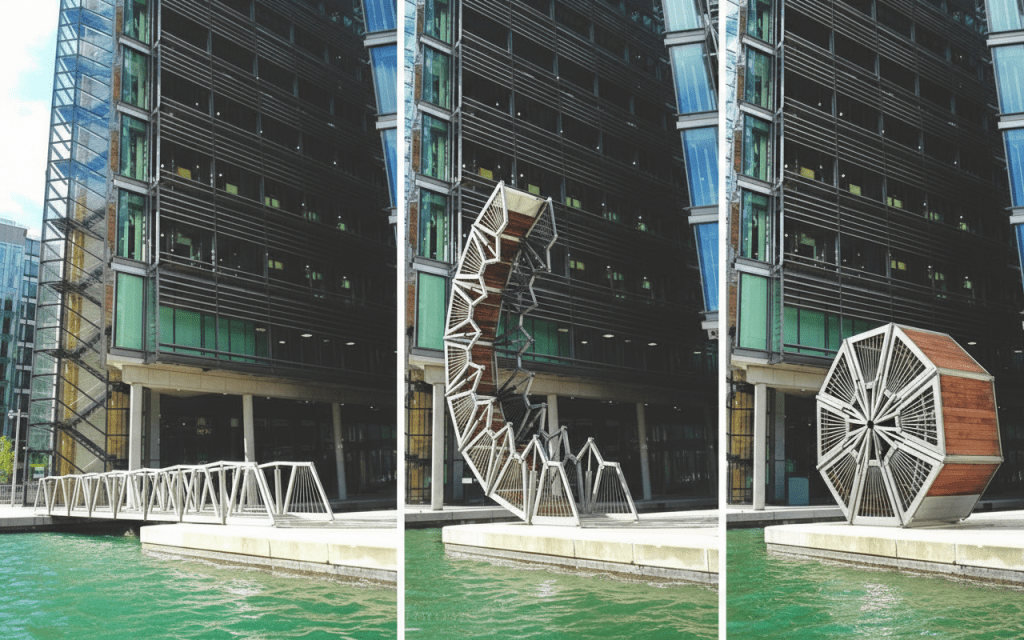

Thomas Heatherwick’s Rolling Bridge, completed in 2004 at Grand Union Canal Paddington Basin, London, (image above) is one of the most unique bridges in the world. A small pedestrian crossing, it is designed to curl up to allow boats through the inlet and uncurl again over the water. “Accept that how people feel about a building is a critical part of its function” in Thomas Heatherwick’s book Humanise.

Buildings are companions, capable of levity as much as shelter.

As de Botton insists, “we are, for better and for worse, different people in different places” . By that standard, purely functional architecture denies our multiplicity—it flattens our capacity for wonder. To “humanise” space, we must allow buildings to laugh a little, to wink at their inhabitants, to be clever without cruelty.

To build with wit is to build with understanding—to make space not just for living, but for feeling alive.

Image: Rolling Bridge 2004, Grand Union Canal Paddington Basin, London. Designed by Heatherwick Studio, © Heatherwick Studio